i

When I used to work at a pawn store, I became very good at reading people. With a glance, you could get a pretty good idea about someone’s habits, socio-economic status, and if you want to get really into, how many kids they had and what ages they were. A sane person would call it stereotyping, a market analyst would call it demographing. It’s not an exact science, at least not when your mentor comes from a long line of pawn store employees rather than formally accredited Ph.D. holding social scientist. My Sherlockian talents were never used to catch murderers, instead, I was a small cog in a vast machine of tearing shiny objects away from people (for revealing and shocking exposé on the topic, please refer to this video).

It’s kind of like counting cards, once you know what’s already out on the table you can start making assumptions for the rest of the deck. But while you may have a really good idea, you’ll never know what the top card is going to be until you see it. But I was good at it. Really good at it, and ergo was really good at my job.

Let’s say a pretty, older woman walks up to me. She’s wearing earrings and a nice sweater. From her knock-off Gucci tote she pulls out a sandwich bag full of jewelry and asks how much I think it’s worth. I can already tell you that the contents of the bag have a really good chance of being entirely 14k gold. I know she’s just curious about how much it can be but ultimately doesn’t really care. I know she’s going to settle on the first number I throw out there. What she doesn’t know is the value of everything she has, and what she doesn’t know is how much I’m going to lowball her. But it’s going to be a lot, and I’m going to make out like a bandit.

But maybe I’m wrong. Maybe she’s done her homework. Maybe she’s not sure how much it’s worth now, but she remembers how much she’s paid for it. And maybe, just maybe, if she’s smart and if she’s the aggressive type she’ll ask if I can do better. I’ll ask what number did she have in mind, and she’ll try to negotiate with me. I’ll try to find the middle ground between my original number and her number. Then I’ll throw out an offer that ends with a 5 or a 0 because people love and I mean love 5s and 0s. There’s a really good chance, she’ll accept and if she isn’t satisfied maybe she’ll ask for a little bit more. I’ll succumb to her demands and she’ll think she’s beaten the system. She really hasn’t. The system’s built-in contingency is to cheat her from the start, with the only real way to avoid getting swindled is avoiding the game entirely.

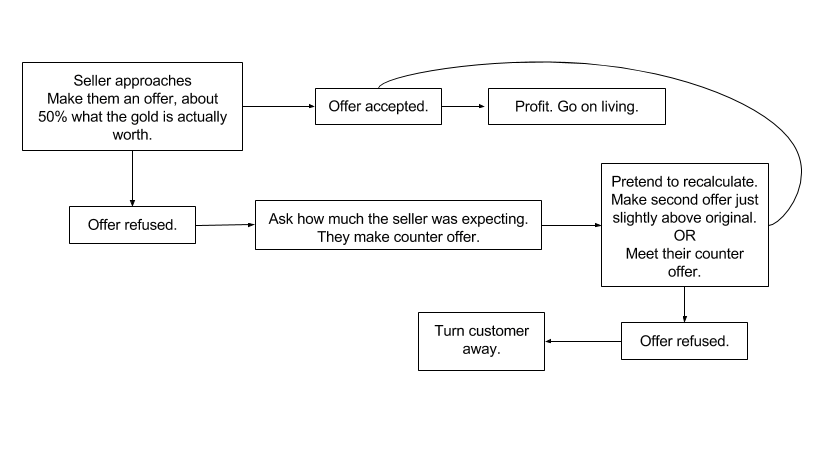

For those a little lost, it kind of looks like this:

My need to read people lessened, but I still catch myself looking at someone and asking the same line of questions (How are their shoes? Are they wearing a wedding ring? What kind of clothes are they wearing? How much jewelry are they wearing? Do their clothes look aged?). It’s not going to make me loads of money anymore, but it gives me a good idea how I can still influence situations that require more finessing. I realized you could manipulate people so easily by giving them gentle ultimatums. Don’t give people a choice, instead give them options because the choice has already been made.

ii

I was lucky to walk away from my car accident. Literally. Besides surviving, my leg was lacerated terribly, and looking at the photos, there’s a small, empty space on the driver’s side just big enough for my leg, otherwise, it would have been crushed. But besides the pain and difficulties walking on it, I had nightmares of headlights jolting me awake. There were post-traumatic episodes and fears of driving at night. My father suggested that I submit a pain and suffering claim to my insurance, thinking that getting a large sum of money would make me feel better regardless of my lack of physical and mental stability. He was right by the way, I love money.

He set up the meeting, and the agent was going to come to the house to negotiate a sum. I figured I had this. Negotiating is what I’d been doing for the last four months at the pawn store, and I had plans to get that insurance company broke. In hindsight, I really wish my dad was with me. The moment there was a knock on my door, all my battle strategies vacated.

She was mousey and dispassionate. She wore thin glasses with stringy, brown spaghetti hair draping over them, and she had an air about her that left me with the impression that I was wasting her time. She was not particularly nice. There were no hints of amiability, and despite the insurance company’s positive slogan and family-oriented mindset, she exuded none of that. And because of the commonality of her name and the unpleasant twenty minutes I spent with her, I have no fear telling you that her name was Mary Smith.

Mary was all about business, and that was my first fault because I assumed that walking through the door was going to be something human. She pulled out my case file and began to get to work, telling me the specifics of things I already knew. Eye contact was limited. She spent a good deal looking at her phone. Mary Smith explained to me how the company handles pain and suffering claims, saying they’d be more than happy to help with my grievances but were limited, roughly to the tune of $10,000.

Before I even realized it, she had initiated negotiations. The first number was the one I wasn’t allowed to touch. It was the number I was supposed to get out of my head right now because she wasn’t going to agree to it.

“How much do pain and suffering claims usually pay out,” I asked, looking for a bottom.

“Three-thousand,” she said without missing a beat. So now I’m standing in the range of $3,000 to $10,000. Find your parameters, work within them. “Do you have a number in mind?”

She was callous. There was no empathy in her tone. I was taken aback by the question, and that was my biggest mistake. Ask any pawn dealer. Emotions are never factored into a deal. Nobody cares it was grandma’s necklace, or how important your grandfather’s gold teeth were to him. You’re not going to get more dollars telling us about your mother’s jewelry that you found hidden underneath floorboards or how this genuine silverware was the talk at your grandparents’ wedding. Numbers don’t give a shit about how personal something is, and Mary Smith didn’t give a shit about me. I was a name and a number that separated her until her next appointment with a different name and a different number.

I looked right at her and said flatly, “Well, I never thought to put a price tag on my well being.”

Nothing rocks your sense of worth quite like a numeric value. Even as I was mulling it over, this was still a job for Mary Smith and she was here to make a deal.

“So…. do you know how much you wanted or…”

She was never going to see me as a person. I could tell her about the nightmares and the PTSD, the leg and the bills, and how my beautiful Crown Victoria was smashed in like an accordion but it wouldn’t have mattered. Then I thought about all the people I put in the exact same position. Then meekly and embarrassed, I asked for $5,000. I overshot her minimum by two grand, but then I reminded myself about the contingencies involved. I was never going to walk out of this a winner. Even with the check in hand, it still didn’t feel like a victory.

In a string of hard lessons learned, this one was probably the hardest, knocking me right in the adulthood. When it comes to money trust is taut, if not totally absent. The human thought process ascends into a purely logical headspace that will chew through any obstacle in its path, be it morals, relationships, or people. Ultimately, the lesson is such: if you plan on being a jerk about money, make sure you’re the biggest jerk in the room.